संपादक की पसंद

-SUNITA NARAIN

WRITE this with considerable anguish. In June, we will come together in Stockholm, marking 50 years of global environmental consciousness. The meet is

to celebrate interdependence and the need for a global compact for planet Earth. But more than ever, such events have virtually become a dialogue among the deaf. The world, it seems, lives on two different planets. There is deep division, polarisation and a lack of understand- ing of each other’s concerns.

Let me tell you what has left me so troubled and has, once again, told me just how much we must learn to listen to each other. As you know, parts of India have been going through an intense, burning heatwave. It has been a living hell in my city Delhi, as temperatures have touched 47˚C. Even as I say this, I know that people like me, who live in relative thermal comfort, are not so badly

ocean acidification—reached record levels in 2021.

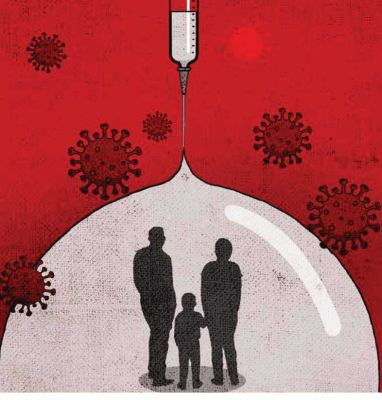

What, then, are the options? One, provide affordable electricity to all so that people can cope with these temperatures; two, build homes with better insulation and ventilation to improve thermal comfort; three, plant trees for shade; and four, increase storage of water for drinking and irrigation. These will also cool our cities’ microclimate. But there are enormous limitations. There is no way we can live or adapt to the rising temperatures that we are beginning to see. It is also clear that the poor in our world are the ones most impacted by this.

But my anguish is not only because of the dire conditions I see in the world around me. As a climate change activist and environmentalist, it makes me realise that I have failed—we all have failed—to make things better. What rubs salt to the wound is when I get inter-

hit. It is the millions who work out in the sun—from farmers to construction workers to all those who cannot afford electricity to even power a fan—are the worst sufferers. They are bearing the brunt of the inferno that has hit work, made people ill, taken lives and burnt and shriveled up part of the wheat crop.

Scientists point out that this time the temperature rise was way too early in the year—in March as against May—making the heat impact more devastating. They connect it to the abnormal behaviour of Pacific Ocean currents, La Niña, which

Instead of asking India about its measures to combat the severe heatwave, western media would do well to acknowledge that the richest countries—their countries—are the cause of the problem

view calls from western media wanting to find out more about the devastating heat conditions. The most predictable question, after the first few enquiries about life and death, is what is India doing to combat climate change. Then comes the query, why does India continue to use coal for its electricity? And then the final one—this one takes the cake—is to ask (or say) that power demand in this heat will go up, which will mean more burning of coal.

What do I have to say about that?

What can I say?

How do I explain that India’s contribu-

have been unusually prolonged, leading to the heat- waves. There is also evidence about changes in the Western Disturbance—the winds from the Mediterra- nean—which are, in turn, influenced by the changes in the Arctic jet stream. The Western Disturbance would bring rain to the Indian subcontinent during this early summer period, reducing the heat’s impact. But this year, the Western Disturbance has been weak. It is still not clear if this is a long-term trend, but what is abso- lutely clear is that there are clear and attributable links between the heatwave and global climate change.

So, things are bad, very bad. It is also certain that we in India must learn to do things differently, knowing that this heat will only get worse. “The State of the Global Climate 2021” report by the World Meteorological Organization, released in May 2022, grimly tells us that the four key indicators of climate change—greenhouse gas (GHG) concentration, sea level rise, ocean heat and

tion to GHG emissions is insignificant by any parameter. How do I explain that the stock of emissions in the atmosphere, which is tipping us over and leading to this heatwave, is not of India’s making. How do I explain that we need to discuss reparations and not blame the poor, or even the relatively rich, in India. How do I explain that the global media powerhouses need to get real about the impacts of climate change on countries like India—my country. That we must and will do more to reduce GHG emissions in our own interests, but what we must discuss today is how the richest countries—their countries—are the cause of the problem, and that we must begin to discuss not just how they will reduce emissions at scale but also the need for paying for this loss and damage to the rest of the world. This is the inconvenient truth that is not heard. We can scream, but that part of the world is not listening. This has to change if we want a better world. If we want our world to survive.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)