संपादक की पसंद

While the SC cannot be blamed in any way for why and how this degradation of Indian democracy originated, it has, in recent years, done little to stop or stem it.

If the forces of authoritarianism and sectarian bigotry continue to gather momentum, and the Supreme Court does little or nothing to check them, then the verdict of history and of constitutional scholarship will be even harsher than it is at present.

Honourable Judges,

This letter is written with respect as well as in anguish. I write as a historian and as a citizen, concerned in both capacities with the growing lack of faith among many Indians in the functioning of the Supreme Court (SC). Let me say straight away that this is part of a wider degradation of Indian democracy, in which the Court is by no means the central actor. Other (and possibly more serious) manifestations of this degradation are the politicisation of the civil service and the police; the creation of a cult of personality; the intimidation of the media; the use of tax and investigative agencies to harass and intimidate independent voices; the refusal to do away with repressive colonial-era laws and instead the desire to strengthen them; and not, least, the undermining of Indian federalism by the steady whittling down of the powers of the states by the Centre.

I should also make it clear that this ongoing degradation of Indian democracy is not the fault of one party or one leader alone. Rather, these perversions of the democratic process were set in motion by the Congress Party when it was in power at the Centre; and they have been further deepened under the rule of the Bharatiya Janata Party since May 2014.

While the SC cannot be blamed in any way for why and how this degradation of Indian democracy originated, it has, in recent years, done little to stop or stem it. Some examples of its failures in this regard have been the Court’s refusal to strike down laws like UAPA that should have no place in a constitutional democracy; its unconscionable delay in hearing major cases (such as with regard to election funding and the Citizenship Amendment Act); and its denial of basic human rights to the children and students of Kashmir, deprived for a full year of access to education and knowledge as a consequence of the longest internet shutdown in the history of any democracy. Constitutional scholars and practising lawyers can perhaps multiply these examples manifold.

Opinion | Judiciary should not unwittingly lend its shoulders for somebody else’s gun to rest and fire

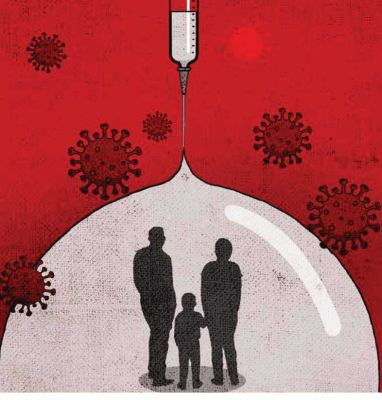

The COVID-19 crisis has seen a further acceleration of this dangerous trend towards authoritarianism and the centralisation of power. The Union government and the ruling party have used the crisis to further promote the cult of personality, to further diminish the powers of state governments, and to further attack the free press. Regrettably, as the hearings and orders of the past few months show, the Supreme Court seems unable or unwilling to check these ominous trends.

The failure of the SC is in part a failure of leadership. That one serving chief justice could tell a daughter wishing to see her mother who had been detained under a draconian act to be careful about the cold, and that another serving chief justice could tell migrant workers left jobless after the unplanned lockdown that since they were being given some food they should not ask for wages — that such callous and unfeeling remarks could come from the chief justice himself reflect poorly on the Court. And that, in the less than six years that the current government has been in power, one chief justice has accepted a Governorship immediately on retirement, and another has accepted a Rajya Sabha seat, also immediately on retirement, reflect even more poorly.

Yet one cannot blame the top man alone. It may be that the powers of the so-called Master of the Roster are imperfectly defined, and can lead themselves to widespread misuse by the incumbent (as the press conference held by J Chelameswar et al in 2018 asserted). But, if the Court is complicit in the steady, continuing and accelerating degradation of our democratic processes and democratic institutions, this cannot be attributed entirely to the chief justices. I think the time has come for all the serving justices in the highest court of the land to think seriously about the ever-increasing gap between their calling as defined by the Constitution, and the direction the Court is now taking.

The reputation of the Supreme Court of India today may be at its lowest ebb since the Emergency. That is the clear impression one gets from the writings of our top constitutional scholars. Thus, in a commentary on the last chief justice, Gautam Bhatia writes that “under his tenure, the Supreme Court has gone from an institution that — for all its patchy history — was at least formally committed to the protection of individual rights as its primary task, to an institution that speaks the language of the executive, and has become indistinguishable from the executive” (The Wire, March 16, 2019). Meanwhile, Pratap Bhanu Mehta has observed: “We look to the Supreme Court for a semblance of constitutional deliverance. We have no idea how a court will rule. But one of the lessons of our recent history is that we misunderstand how a Supreme Court functions in a democracy. The Supreme Court has badly let us down in recent times, through a combination of avoidance, mendacity, and a lack of zeal on behalf of political liberty” (IE, December 12, 2019). Most recently, in writing of “the transformation of the Indian state into a repository of repression”, Suhas Palshikar comments that “this political transformation would not have been so easy without the willingness of the judiciary to look the other way, and occasionally join in the project” (IE, August 4).

These assessments are shared by many of the wisest and most experienced members of the Bar, who —unlike the scholars cited above — are not at liberty to express their anxieties in public. I broadly endorse the assessments of Bhatia, Mehta and Palshikar myself. At the same time, as a historian, I know that while institutions do decay, they can also be revived. In the case of the Supreme Court, its capitulation to the state and politicians in power in the 1970s, before and during the Emergency, was followed by a steady assertion of its independence and autonomy in the 1980s and 1990s. One must likewise hope that the current decline may be arrested and reversed in the years to come. If, on the other hand, the forces of authoritarianism and sectarian bigotry continue to gather momentum, and the Supreme Court does little or nothing to check them, then the verdict of history and of constitutional scholarship will be even harsher than it is at present. In that case, the Court of today may come to be viewed by future generations of Indians not merely as an executive Court, but as a collaborationist Court.

Hence this letter, a desperate cry from a historian and citizen who sees his country’s democracy and constitutional framework crumble before his eyes.

Sincerely yours,

Ramachandra Guha

This article first appeared in the print edition on August 12 under the title “Honourable judges”. The writer is a Bengaluru-based historian (indianexpress.com)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)